Imaginary Home[s]

CORE IV—HARVARD GSD

SPRING 2021

INSTRUCTOR: JENNY FRENCH

COLLAB : DARIEN CARR

SPRING 2021

INSTRUCTOR: JENNY FRENCH

COLLAB : DARIEN CARR

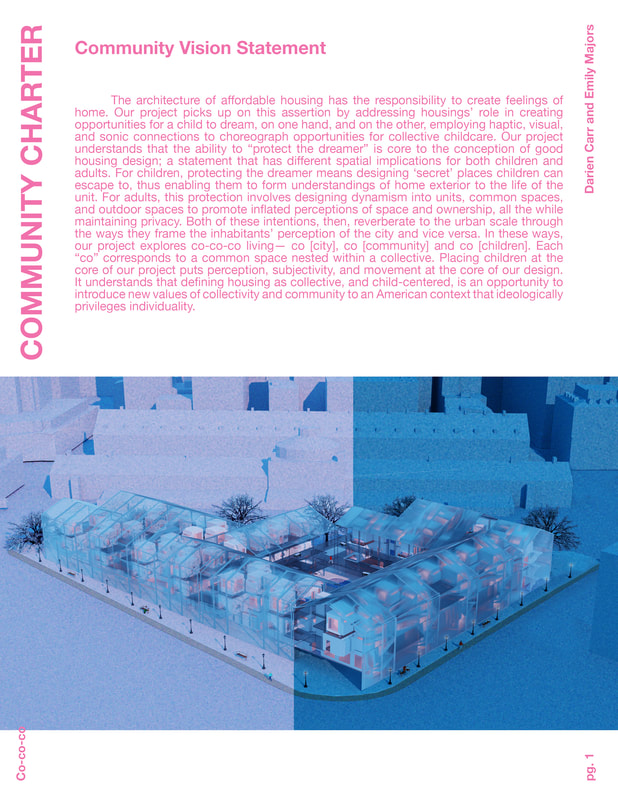

In the Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachleard describes the chief benefit of the house: “the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” Internationally, but also in the context of America, the act of not protecting dreams and imaginations, is a catastrophic failure of housing today; which is evident when we think about it in relation to raising kids. Jean Piaget explains that a child’s cognitive development happens in four stages through a process known as “discovery learning”— the idea that children learn best through doing and actively exploring, setting the stage for them to learn about the world in a gradual, controlled, manner. When we look at examples of housing failing to protect a child’s imagination, however, it’s clear many kids don’t have that privilege. In response, they find ways to adapt. They find spaces [homes] outside of where they live [houses] to dream from — from abandoned buildings, to neighbors houses, alleyways, terraces, and even underneath staircases. Imaginary Home[s] is concerned with designing an architecture to hold these journeys between, and pathways along, a child’s imagination. Through the conflation of corridors and rooms — portals and destinations — our design blurs the line between house and home. The typical housing complex prioritizes large living spaces connecting to a centralized, efficient system of circulation, while our project does the opposite. Re-purposed circulation spaces produce a series of architectural leftovers that modulate according to scale. For the city, an enlarged interior corridor produces an event space for the market across the street, while for families, areas beneath staircases become kid-sized playrooms. Our proposal asserts that the future of human shelter prioritizes the protection of dreams through the crannies, nooks and other scales of architectural leftovers it emphasizes— containers for imaginations still in motion.

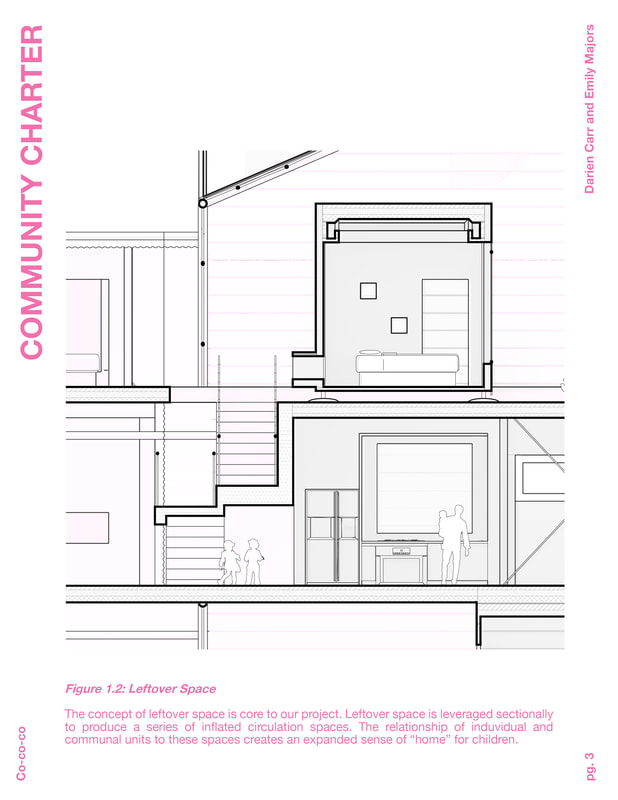

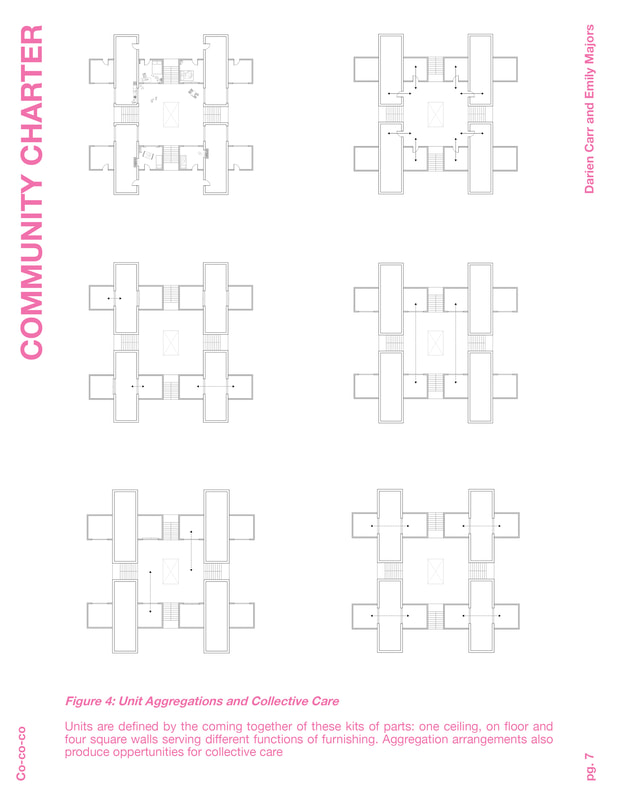

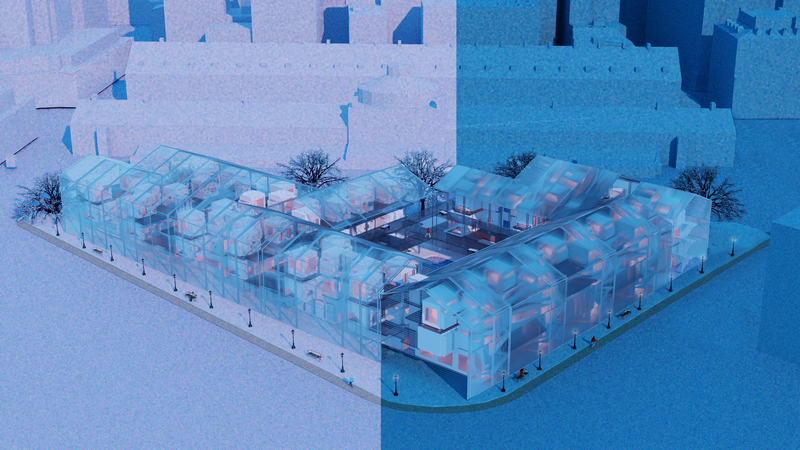

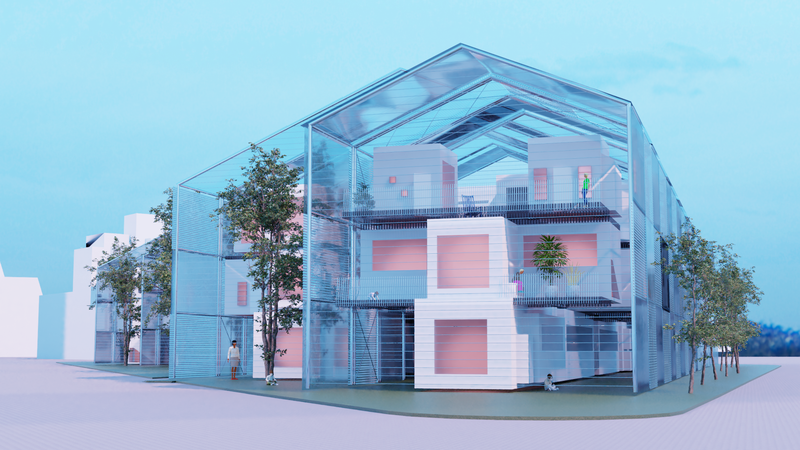

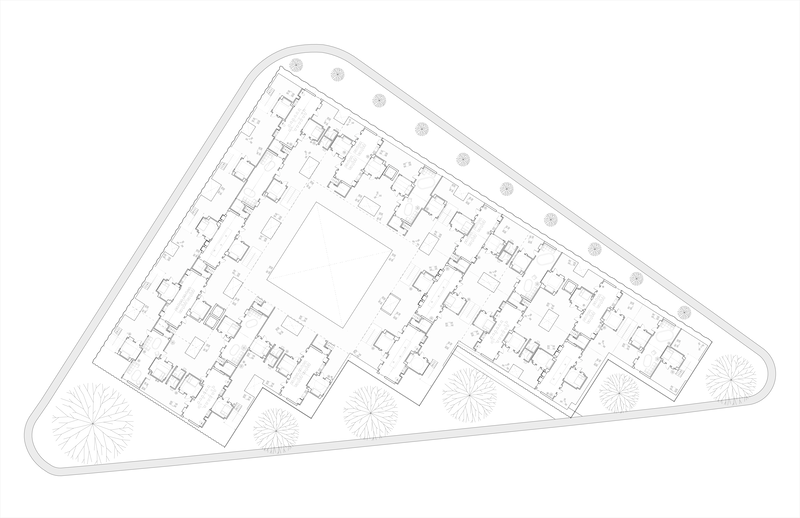

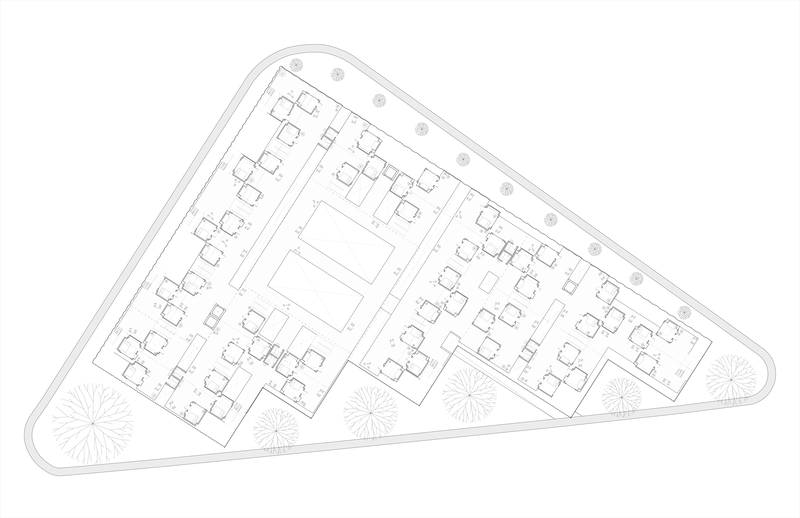

The project is composed of a series of wall types that come together to form a variety of enclosure possibilities. Private unit wall types include recesses for beds, closets, shelving, storage, and apertures, freeing the floor space for spacious living. Communal wall types include cavities for cooking, dining, washing, and lounging. When aggregated within the grid of the housing complex, they generate nooks and crannies for play, adventure, and exploration. The grid arrangement of these private and communal components sets up visual relationships between spaces in order to encourage collective care throughout the complex. Tenants can control visual access through curtains or blinds. The assortment of wall types blurs the boundaries between inside and out, producing a reciprocity between house and home. This system enables the exteriors on one scale, to become the interiors on another, and vice versa.

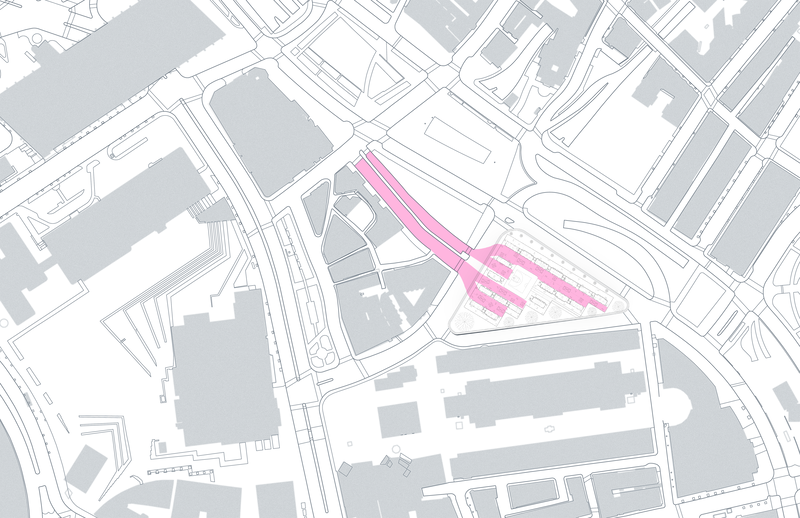

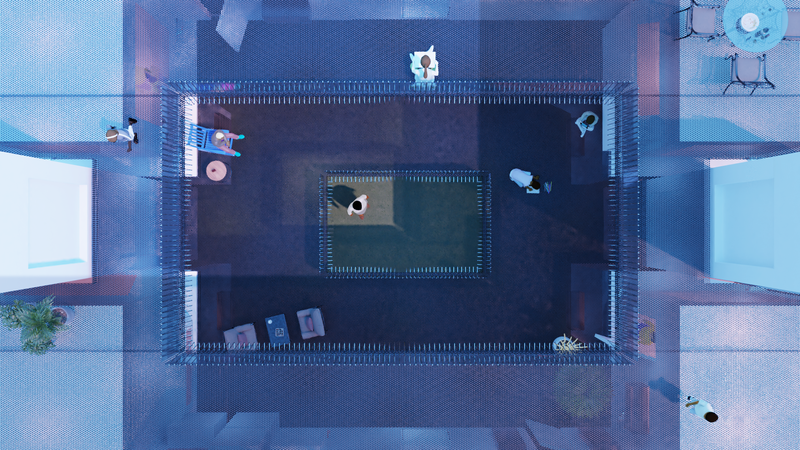

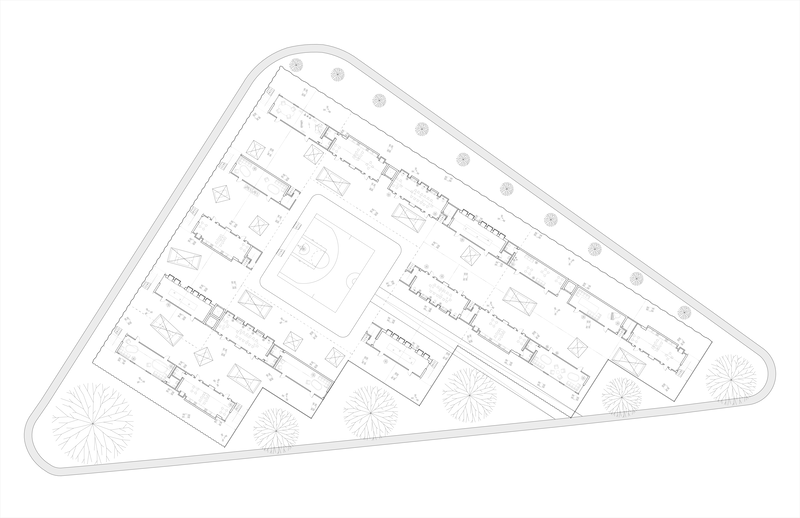

The expanded circulation space manifests in plan. On the ground floor directional striated bars produce leftover space on a larger scale, connecting the complex to its broader context of Downtown Boston through inflated urban promenades. The directionality of these striated leftover spaces allows the adjacent Haymarket to spill into the housing complex, inviting tenants to engage with the city and for the city to engage with the tenants. Zooming into this ground floor plan, the program consists of a variety of communal programs such as, kitchens, lounges, co-working spaces, laundry rooms, and a basketball court. Some of these spaces are shared with the city. On level two, the direction of this striation switches, and living units are introduced, creating shared patios between residents. The spatial character of each one is different, due to its proximity to the various wall types. The third plan demonstrates how walls are used to create different kinds of living arrangements, some more public and some more private. The people living here use corridors and stairs to access communal areas and patios. These “spatial leftovers” are interpolated to create series of nested communities. Communal living becomes extended to “Co-Co-Co-Living” (1) Co-[City], (2) Co-[Community], and (3) Co-[Children]

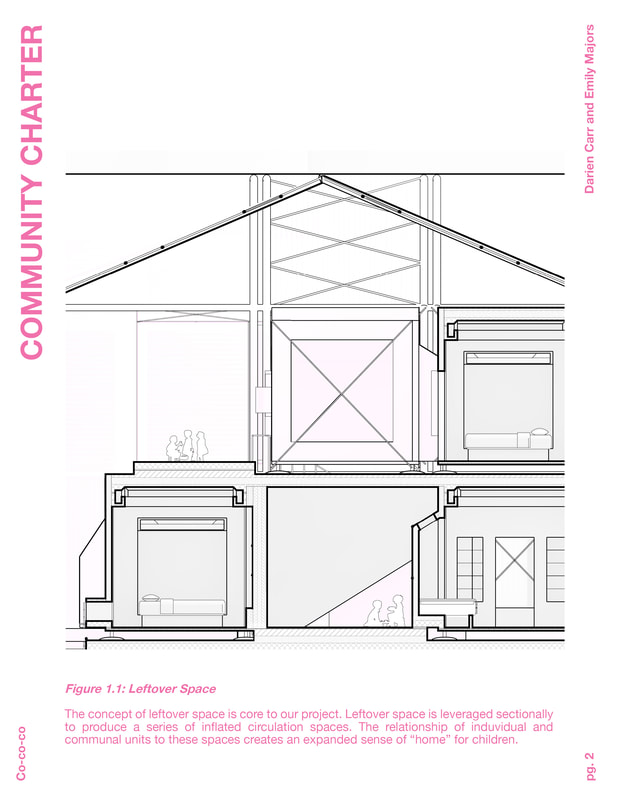

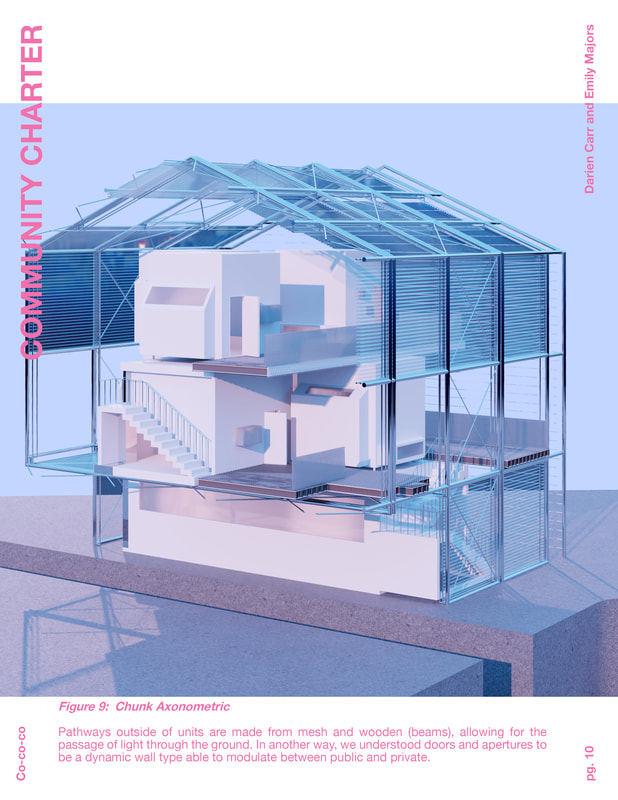

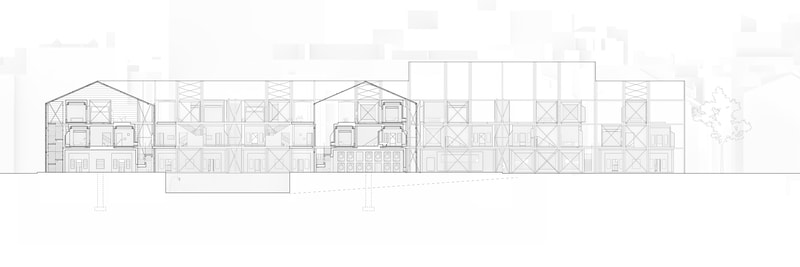

Structurally, the project is accomplished through the stacking of CLT units and moments of cantilevering branching off from these stacks, a system completely independent from the gabled, metal superstructure. The interstitial spaces between the stacked CLT units and gabled superstructure present an opportunity for informal inhabitation and the extension of home beyond the confounds of the house. Overall, the project privileges the preservation of room like qualities found in enlarged circulation spaces. The area underneath staircases produces a kid sized playroom while the interstitial spaces between units produce “secret passages” between different destinations. The relationship of these

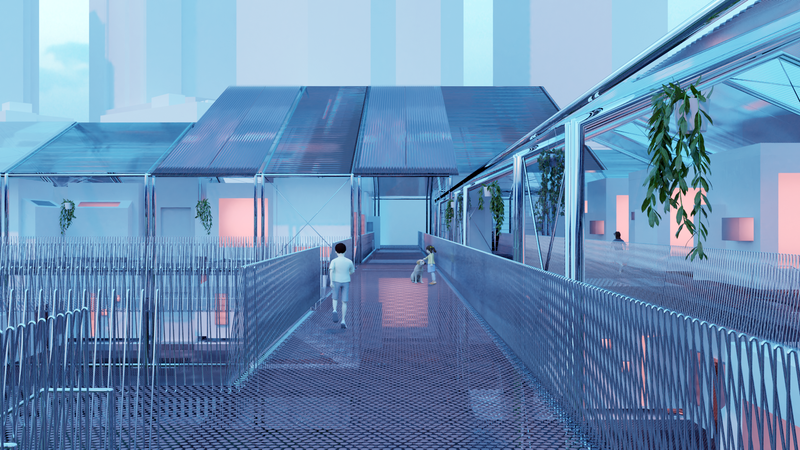

kinds of spaces to individual and communal units creates an expanded sense of “home” for children. Pathways outside of units are made from mesh and wooden beams, allowing for the passage of light through the ground. In another way, doors and apertures can be understood to be a dynamic wall type able to modulate between public and private. The mesh pathways act as a hybrid between the dialectic of steel and wood, reality and fantasy. The transparency of the mesh and spacing of the wooden beams allows light to pass through floor plates.

In conclusion, designing for imaginations still in motion entails an expansion of the mundane through the ways the built environment is perceived. By imagining a modular architecture of expanded circulation spaces, this proposal seeks to serve as another kind of window into a child’s imagination through the nooks, crannies and other types of architectural leftovers it emphasizes, transforming pathways into destinations for a kid to imagine from.

The project is composed of a series of wall types that come together to form a variety of enclosure possibilities. Private unit wall types include recesses for beds, closets, shelving, storage, and apertures, freeing the floor space for spacious living. Communal wall types include cavities for cooking, dining, washing, and lounging. When aggregated within the grid of the housing complex, they generate nooks and crannies for play, adventure, and exploration. The grid arrangement of these private and communal components sets up visual relationships between spaces in order to encourage collective care throughout the complex. Tenants can control visual access through curtains or blinds. The assortment of wall types blurs the boundaries between inside and out, producing a reciprocity between house and home. This system enables the exteriors on one scale, to become the interiors on another, and vice versa.

The expanded circulation space manifests in plan. On the ground floor directional striated bars produce leftover space on a larger scale, connecting the complex to its broader context of Downtown Boston through inflated urban promenades. The directionality of these striated leftover spaces allows the adjacent Haymarket to spill into the housing complex, inviting tenants to engage with the city and for the city to engage with the tenants. Zooming into this ground floor plan, the program consists of a variety of communal programs such as, kitchens, lounges, co-working spaces, laundry rooms, and a basketball court. Some of these spaces are shared with the city. On level two, the direction of this striation switches, and living units are introduced, creating shared patios between residents. The spatial character of each one is different, due to its proximity to the various wall types. The third plan demonstrates how walls are used to create different kinds of living arrangements, some more public and some more private. The people living here use corridors and stairs to access communal areas and patios. These “spatial leftovers” are interpolated to create series of nested communities. Communal living becomes extended to “Co-Co-Co-Living” (1) Co-[City], (2) Co-[Community], and (3) Co-[Children]

Structurally, the project is accomplished through the stacking of CLT units and moments of cantilevering branching off from these stacks, a system completely independent from the gabled, metal superstructure. The interstitial spaces between the stacked CLT units and gabled superstructure present an opportunity for informal inhabitation and the extension of home beyond the confounds of the house. Overall, the project privileges the preservation of room like qualities found in enlarged circulation spaces. The area underneath staircases produces a kid sized playroom while the interstitial spaces between units produce “secret passages” between different destinations. The relationship of these

kinds of spaces to individual and communal units creates an expanded sense of “home” for children. Pathways outside of units are made from mesh and wooden beams, allowing for the passage of light through the ground. In another way, doors and apertures can be understood to be a dynamic wall type able to modulate between public and private. The mesh pathways act as a hybrid between the dialectic of steel and wood, reality and fantasy. The transparency of the mesh and spacing of the wooden beams allows light to pass through floor plates.

In conclusion, designing for imaginations still in motion entails an expansion of the mundane through the ways the built environment is perceived. By imagining a modular architecture of expanded circulation spaces, this proposal seeks to serve as another kind of window into a child’s imagination through the nooks, crannies and other types of architectural leftovers it emphasizes, transforming pathways into destinations for a kid to imagine from.